Accelerating Tensor Computations in Julia with the GPU

How my code went from one week to one hour runtimes

Introduction/Roadmap

Last year at JuliaCon, Matt Fishman and I gave a talk about our ongoing effort to port the ITensor code from C++ to Julia. At the time, I mentioned that we had begun trying to integrate a GPU-based tensor contraction backend and were looking forward to some significant speedups. We ended up completing this integration, and saw runtimes for representative parameters go from one week to one hour. In this post I'm going to go over:

- The physics problem we were writing code to solve

- Why the GPU is a good candidate to accelerate our simulations to solve this problem

- Why Julia is a natural choice if you want to take advantage of the GPU easily

- How, after we wrote the initial implementation, we made it faster by removing roadblocks

- Some final thoughts about why this worked out well for us

What is ITensor

To understand why we thought this would be fruitful, and some performance traps we could already anticipate before writing a single line of GPU code, you have to understand a bit about the problem we're trying to solve. Tensor network algorithms are a very active area of research at the intersection of condensed matter physics, high energy physics, quantum information, and computer science. DMRG, which is the most successful numerical method for condensed matter systems in 1D, wasn't originally formulated as a tensor network algorithm, but “tensor network speak” turns out to be a natural language with which to discuss DMRG and its descendants. (If you're not sure what it's meant to solve, imagine a long chain of quantum objects, each with a fretful relationship with their neighbours. Will they overcome their differences and work together to form a magnet, or continue arguing with each other and fail to come to a consensus? DMRG is an efficient way to answer this question.) All this is to say that there's this class of algorithms physicists (and increasingly computer scientists) are interested in and they work well.

The driving idea of a tensor network algorithm is to take some high-dimensional optimization problem (solving for groundstates (eigenvectors corresponding to the minimal eigenvalue) of quantum many body systems is an example of this, since the full dimension of the system grows exponentially in the number of constituent particles) and compress it down to a much lower dimensional problem while retaining most of the important features. We do this by taking a d^N length vector, where d is the number of degrees of freedom of each constituent, and N is the number of constituents, and breaking it down into a set of multidimensionsal tensors, the number of which hopefully scales like N or at least much less than exponentially.

If you've studied linear algebra before, you've seen some simple examples of tensors: scalars, vectors, and matrices. We say a scalar is a 0-rank tensor, a vector a 1-rank tensor (since it has one index), a matrix a 2-rank tensor (since it has two indices), and then there are higher rank tensors, with three or more indices. When we multiply two matrices A_ij and B_jk together to get C_ik, we're performing a “tensor contratction”, and we compute C_ik by ssumming over indices i and j. Similarly, if we had high-rank tensors A_ijkl and B_lmin, we could contract them to get C_jkmn - again, by summing over indices i and l.

Most tensor network algorithms are based on performing this decomposition and then iteratively improving it towards a target vector. Usually in physics that target is a physical state, but tensor networks have also been used for machine learning tasks and can represent quantum error correcting codes as well.

ITensor is a C++ package dedicated to providing both high level algorithms using tensor networks, like DMRG, and the low-level building blocks to create your own. ITensor makes it easy to create tensors out of indices, perform linear algebra factorizations (such as QR or SVD) on them, without forcing the user to worry about index ordering. You can read the ITensor tutorials for more information or watch our talk.

Why use the GPU

It seems pretty reasonable that you could expect a speedup for many tensor network algorithms by using a GPU. By permuting indices, it's possible to reduce all contraction operations to matrix-matrix or matrix-vector multiplications, at which the GPU excels. Most tensor network algorithms have runtimes dominated by such contractions or by SVD. However, there are some performance gotchas we always need to consider when using the GPU:

- The device has comparatiely low memory. The most expensive cards have 32GB of onboard RAM, which is a lot, but many state-of-the-art DMRG calculations require over a terabyte of RAM or checkpointing by writing intermediate information to disk.

- There's high latency and low bandwidth for memory transfers. If we absolutely have to copy memory from the host CPU to the device, we should try to do it all in one big blob, and not in many small chunks. Although the GPU can overlap computations and memory transfers writing code to handle this can be a bit complex.

- The performance for single precision floats is much better than for double precision. Although we'll probably see a perfomance boost for doubles, it won't be as dramatic as for single precision

Float32.

In addition, there is a danger in the most naive approach to handling tensor contractions, which is to just permute all involved tensors into the index layout necessary to write the operation as a matrix-matrix multiplication, and then sit back and call GEMM. Although in many cases this will work quite well, especially if the permutation doesn't involve many indices, there are plenty of bad cases where a great deal of time could be spent alllocating destination arrays and permuting source arrays into them. The risk of this increases with the average number of indices on each tensor (since there are more “bad” permutations available).

For these reasons, we weren't sure if the GPU would be a good choice for my current reseach project. You can read the physics details here. We have a C++ implementation of this code which is CPU only and runs about 5000 lines. One of my goals with the project was to eventually open source the code in the hope that others might find it useful or improve it. However, C++, despite being a great langauge, can be intimidating to many people. I have some experience writing C code that uses CUDA which, despite the powerful API and really granular control over the device the programmer is provided, can also be intimidating and require you to keep a lot of balls in the air while you're writing the code. But the C++ solution, stuck on a single node as it was, with all parallelism coming from CPU BLAS spread over 28 cores, was taking up to a week to run to get a decent picture of the converged result. This was pretty frustrating from a development perspective because it meant the debug cycle of “something's wrong” - “OK, think I found it” - “is this a fix?” - “nope, something's still wrong” had to take place over multiple days.

Since Miles (the original author of ITensor) and Matt were already thinking of rewriting ITensor in Julia (see our talk for the motivations for this decision), I decided I would try to help and maybe try to add some GPU support to the new package. Many tensor network algorithms, not only this one, are dominated by tensor-tensor contractions as mentioned above. And since I had already had some experience working with Julia's GPU programming/wrapping infrastructre in CuArrays.jl, I thought it wouldn't be so hard to integrate a GPU based tensor operations backend to ITensors.jl. (In fact, we sometimes want to add or subtract tensors, not just contract them.)

Our first approach, and one I don't have benchmarks for, was the naive method described above - just permute everything and call CUBLAS's general matrix-matrix multiplication routine. In general, handling GPU memory with CuArrays.jl was very easy. An ITensor is essentially an opaque Vector with some indices along for the ride, which tell you in what order to index elements of the Vector. It's analogous to CartesianArray for those who have used Julia's multidimensional array support. Since our algorithms usually require us to somehow achieve a contraction, QR decomposition, and addition, we thought treating the ITensor storage as essentially a blob you can permute and give to multiplication API calls would be enough. Usually in these algorithms you're not often accessing or manipulating single elements or slices of the ITensor (although this is possible to do and easy in both the C++ and Julia versions), just the tensors themselves.

Here's the sum total of the code I needed to get a barebones cuITensor that you could move on and off the GPU:

function cuITensor(::Type{T},inds::IndexSet) where {T<:Number}

return ITensor(Dense{float(T)}(CuArrays.zeros(float(T),dim(inds))), inds)

end

cuITensor(::Type{T},inds::Index...) where {T<:Number} = ITensor(T,IndexSet(inds...))

cuITensor(is::IndexSet) = cuITensor(Float64,is)

cuITensor(inds::Index...) = cuITensor(IndexSet(inds...))

cuITensor() = ITensor()

function cuITensor(x::S, inds::IndexSet{N}) where {S<:Number, N}

dat = CuVector{float(S)}(undef, dim(inds))

fill!(dat, float(x))

ITensor(Dense{S}(dat), inds)

end

cuITensor(x::S, inds::Index...) where {S<:Number} = cuITensor(x,IndexSet(inds...))

function cuITensor(A::Array{S},inds::IndexSet) where {S<:Number}

return ITensor(Dense(CuArray{S}(A)), inds)

end

function cuITensor(A::CuArray{S},inds::IndexSet) where {S<:Number}

return ITensor(Dense(A), inds)

end

cuITensor(A::Array{S}, inds::Index...) where {S<:Number} = cuITensor(A,IndexSet(inds...))

cuITensor(A::CuArray{S}, inds::Index...) where {S<:Number} = cuITensor(A,IndexSet(inds...))

cuITensor(A::ITensor) = cuITensor(A.store.data,A.inds)

function Base.collect(A::ITensor)

typeof(A.store.data) <: CuArray && return ITensor(collect(A.store), A.inds)

return A

end

Mostly, this handles different ways of providing the indices, and a few options for the input data type. I assumed that if you called the cuITensor constructor but gave it an input CPU array, you probably wanted that array transferred to the GPU.

That's the easy part. Adding support for some other operations, like QR decomposition or eigensolving, wasn't much harder:

function eigenHermitian(T::CuDenseTensor{ElT,2,IndsT};

kwargs...) where {ElT,IndsT}

maxdim::Int = get(kwargs,:maxdim,minimum(dims(T)))

mindim::Int = get(kwargs,:mindim,1)

cutoff::Float64 = get(kwargs,:cutoff,0.0)

absoluteCutoff::Bool = get(kwargs,:absoluteCutoff,false)

doRelCutoff::Bool = get(kwargs,:doRelCutoff,true)

local DM, UM

if ElT <: Complex

DM, UM = CUSOLVER.heevd!('V', 'U', matrix(T))

else

DM, UM = CUSOLVER.syevd!('V', 'U', matrix(T))

end

DM_ = reverse(DM)

truncerr, docut, DM = truncate!(DM_;maxdim=maxdim, cutoff=cutoff, absoluteCutoff=absoluteCutoff, doRelCutoff=doRelCutoff)

dD = length(DM)

dV = reverse(UM, dims=2)

if dD < size(dV,2)

dV = CuMatrix(dV[:,1:dD])

end

# Make the new indices to go onto U and V

u = eltype(IndsT)(dD)

v = eltype(IndsT)(dD)

Uinds = IndsT((ind(T,1),u))

Dinds = IndsT((u,v))

dV_ = CuArrays.zeros(ElT, length(dV))

copyto!(dV_, vec(dV))

U = Tensor(Dense(dV_),Uinds)

D = Tensor(Diag(real.(DM)),Dinds)

return U,D

end

This weird looking method of getting dV into dV_ is necessary because of the way CuArrays.jl deals with reshapes. As we'll see later it doesn't seem to impact performance too much.

But of course, the big problem we wanted to solve was contractions. Because the CPU code also works by performing the permutation and calling GEMM, it was relatively easy to pirate that over to the GPU:

function contract!(C::CuArray{T},

p::CProps,

A::CuArray{T},

B::CuArray{T},

α::Tα=1.0,

β::Tβ=0.0) where {T,Tα<:Number,Tβ<:Number}

# bunch of code to find permutations and permute α and β goes here!

CUBLAS.gemm_wrapper!(cref, tA,tB,aref,bref,promote_type(T,Tα)(α),promote_type(T,Tβ)(β))

if p.permuteC

permutedims!(C,reshape(cref,p.newCrange...),p.PC)

end

return

end

The design of ITensors.jl specifies that the ITensor type itself is not specialized on its storage type, so that from the user's point of view, they have a tensor-like object contracting with another tensor-like object, and the developers can worry about how to multiply a diagonal-like rank-6 tensor by a sparse rank-4 tensor. This makes it easier for users to implement the algorithms they need to do their research in, and it's one of the library's strengths. All that was needed to allow an ITensor with GPU-backed storage to play nicely with an ITensor with CPU-backed storage was few lines of edge case handling:

function contract!!(R::CuDenseTensor{<:Number,NR}, labelsR::NTuple{NR}, T1::DenseTensor{<:Number,N1}, labelsT1::NTuple{N1}, T2::CuDenseTensor{<:Number,N2}, labelsT2::NTuple{N2}) where {NR,N1,N2}

return contract!!(R, CuDenseTensor(cu(store(T1)), inds(T1)), labelsT1, T2, labelsT2)

end

function contract!!(R::CuDenseTensor{<:Number,NR}, labelsR::NTuple{NR}, T1::CuDenseTensor{<:Number,N1}, labelsT1::NTuple{N1}, T2::DenseTensor{<:Number,N2}, labelsT2::NTuple{N2}) where {NR,N1,N2}

return contract!!(R, T1, labelsT1, CuDenseTensor(cu(store(T2)), inds(T2)), labelsT2)

end

I chose to copy the CPU storage to the device before the addition or contraction, hoping that this would occur rarely and that the performance gain in the main operation would offset the memory transfer time. Ideally this situation should never occur: we absolutely want to minimize memory transfers. However, if a user makes a mistake and forgets a cuITensor(A), their code won't error out. In fact, in the latest version of ITensorsGPU.jl this dubious feature is disallowed, since in my code it was always the result of forgetting to initialize something on the GPU which should have been.

This was enough to get the barebones GPU support working. But I was still worried about the issue with the permutations, especially because the week-long simulations are those which are most memory intensive, and I was worried about running out of space on the device. Could there be a better solution?

CUTENSOR and the story of how computers made my labour useless

Around this time we became aware of CUTENSOR, an NVIDIA library designed exactly for our use case: adding and contracting high rank tensors with indices in arbitrary order. However, this library was, of course, written in C. Luckily Julia makes it pretty easy to wrap C APIs, and we got started doing so in this epic PR to CuArrays.jl. CuArrays.jl already provides nice high- and low-level wrappers of CUDA C libraries in Julia, not only for dense or sparse linear algebra but also for random number generation and neural network primitives. So adding a multi-dimensional array library was a natural fit. During the process of getting these wrappers into a state fit for a public facing library, Tim Besard created some very nice scripts which automate the process of creating Julia wrappers for C functions, automating away many hours of labour I had performed years ago to get the sparse linear algebra and solver libraries working. Sic transit gloria mundi, I guess (generating these wrappers was not a glorious process). Now it will be easy for us to integrate changes to the CUTENSOR API over time as more features are added.

CUTENSOR's internals handle matching up elements for products and sums as part of the contraction process, so the permutations that ITensors.jl performs for a CPU-based ITensor are unnecessary. By overriding a few functions we're able to call the correct internal routines which feed through to CUTENSOR:

function Base.:+(B::CuDenseTensor, A::CuDenseTensor)

opC = CUTENSOR.CUTENSOR_OP_IDENTITY

opA = CUTENSOR.CUTENSOR_OP_IDENTITY

opAC = CUTENSOR.CUTENSOR_OP_ADD

Ais = inds(A)

Bis = inds(B)

ind_dict = Vector{Index}()

for (idx, i) in enumerate(inds(A))

push!(ind_dict, i)

end

Adata = data(store(A))

Bdata = data(store(B))

reshapeBdata = reshape(Bdata,dims(Bis))

reshapeAdata = reshape(Adata,dims(Ais))

# probably a silly way to handle this, but it worked

ctainds = zeros(Int, length(Ais))

ctbinds = zeros(Int, length(Bis))

for (ii, ia) in enumerate(Ais)

ctainds[ii] = findfirst(x->x==ia, ind_dict)

end

for (ii, ib) in enumerate(Bis)

ctbinds[ii] = findfirst(x->x==ib, ind_dict)

end

ctcinds = copy(ctbinds)

C = CuArrays.zeros(eltype(Bdata), dims(Bis))

CUTENSOR.elementwiseBinary!(one(eltype(Adata)), reshapeAdata, ctainds, opA, one(eltype(Bdata)), reshapeBdata, ctbinds, opC, C, ctcinds, opAC)

copyto!(data(store(B)), vec(C))

return B

end

Once these wrappers and their tests were merged into CuArrays.jl, I set about changing up how we were calling the contraction functions on the ITensors.jl side. We decided to do this because within CUTENSOR there were already highly optimized routines for various permutations, and we didn't want to try to reinvent the wheel with our permute-then-GEMM system. Switching to CUTENSOR let us abstract away the permutation-handling, so the code interfacing with CuArrays.jl was much simpler than under our previous approach. Dealing with optional dependencies, as CuArrays.jl would have been for ITensors.jl, is still kind of a pain in Julia, so I made a new package, ITensorsGPU.jl, to hold all the CUDA-related logic. What's nice is that from the end-user's perspective, they just have copy the tensors to the GPU at the start of the simulation and afterwards everything works mostly seamlessly – they don't have to concern themselves with index orders or anything. It frees the user to focus more on high-level algorithm design.

Extirpating memory copies

Copying memory back and forth from the device is extremely slow, and the code will perform best if we can eliminate as many as possible. One way to see how much time the device is spending on them is using NVIDIA's nvprof tool. Working with the cluster means I usually do most of my development over SSH, so I used command line mode, which is really easy:

nvprof ~/software/julia/julia prof_run.jl

This generates some output about how much time the GPU spent doing various things, which is very long horizontally - scroll the box sideways if you can't see the function names:

==1386746== Profiling application: julia prof_run.jl

==1386746== Profiling result:

Type Time(%) Time Calls Avg Min Max Name

GPU activities: 14.02% 12.1800s 80792 150.76us 102.69us 408.00us void sytd2_upper_cta<double, double, int=5>(int, double*, int, double*, double*, double*)

7.44% 6.46842s 5077903 1.2730us 1.1190us 54.367us [CUDA memcpy HtoD]

6.02% 5.22885s 4430677 1.1800us 959ns 7.2640us ptxcall_anonymous19_1

5.06% 4.39301s 178968 24.546us 8.4480us 81.855us void cutensor_internal_namespace::tensor_contraction_kernel<cutensor_internal_namespace::tc_config_t<int=8, int=4, int=64, int=64, int=1, int=32, int=32, int=1, int=8, int=4, int=8, int=1, int=1, int=1, int=1, int=4, bool=1, bool=0, bool=0, bool=1, bool=0, cutensorOperator_t=1, cutensorOperator_t, cutensorOperator_t, cutensorOperator_t, bool=0>, double, double, double, double>(cutensor_internal_namespace::tc_params_t, int=1, int=4 const *, int=64 const *, cutensor_internal_namespace::tc_params_t, int=64*)

4.97% 4.31812s 346589 12.458us 5.4400us 29.088us void cutensor_internal_namespace::tensor_contraction_kernel<cutensor_internal_namespace::tc_config_t<int=8, int=4, int=64, int=64, int=1, int=16, int=16, int=1, int=8, int=4, int=4, int=1, int=1, int=1, int=1, int=4, bool=1, bool=1, bool=0, bool=0, bool=0, cutensorOperator_t=1, cutensorOperator_t, cutensorOperator_t, cutensorOperator_t, bool=0>, double, double, double, double>(cutensor_internal_namespace::tc_params_t, int=1, int=4 const *, int=64 const *, cutensor_internal_namespace::tc_params_t, int=64*)

4.96% 4.31109s 2397744 1.7970us 1.7270us 6.8160us ptxcall_setindex_kernel__26

4.18% 3.63043s 228988 15.854us 5.8560us 28.672us void cutensor_internal_namespace::tensor_contraction_kernel<cutensor_internal_namespace::tc_config_t<int=8, int=4, int=64, int=64, int=1, int=16, int=16, int=1, int=8, int=4, int=4, int=1, int=1, int=1, int=1, int=4, bool=1, bool=0, bool=0, bool=0, bool=0, cutensorOperator_t=1, cutensorOperator_t, cutensorOperator_t, cutensorOperator_t, bool=0>, double, double, double, double>(cutensor_internal_namespace::tc_params_t, int=1, int=4 const *, int=64 const *, cutensor_internal_namespace::tc_params_t, int=64*)

3.41% 2.96655s 2162240 1.3710us 1.2470us 3.4880us [CUDA memcpy DtoH]

2.77% 2.40280s 1827148 1.3150us 1.0870us 7.3600us ptxcall_anonymous19_14

2.70% 2.34219s 1327280 1.7640us 1.5360us 6.5920us ptxcall_setindex_kernel__15

5424,21 96%

...

You can see the memcpyHtoD there, and it's taking up a lot of time! By carefully going through and creating ITensors with the appropriate storage type in internal routines, like so:

# again probably a nicer way to do this

is_gpu = all([data(store(A[i,j])) isa CuArray for i in 1:Ny, j in 1:Nx)

N = spinI(findindex(A[row, col], "Site"); is_gpu=is_gpu)

function spinI(s::Index; is_gpu::Bool=false)::ITensor

I_data = is_gpu ? CuArrays.zeros(Float64, dim(s)*dim(s)) : zeros(Float64, dim(s), dim(s))

idi = diagind(reshape(I_data, dim(s), dim(s)), 0)

I_data[idi] = is_gpu ? CuArrays.ones(Float64, dim(s)) : ones(Float64, dim(s))

I = is_gpu ? cuITensor( I_data, IndexSet(s, s') ) : ITensor(vec(I_data), IndexSet(s, s'))

return I

end

it's possible to dramatically cut down on this, getting a final profiling report of

==3303697== Profiling application: julia prof_run.jl

==3303697== Profiling result:

Type Time(%) Time Calls Avg Min Max Name

GPU activities: 13.78% 19.2803s 343307 56.160us 15.328us 7.2638ms cutensor_internal_namespace::contraction_kernel(cutensor_internal_namespace::KernelParam_double_iden_1_2_false_false_double_iden_1_2_false_false_double_1_double_double_tb_128_128_8_simt_sm50_256)

13.47% 18.8464s 440326 42.800us 15.071us 653.75us cutensor_internal_namespace::contraction_kernel(cutensor_internal_namespace::KernelParam_double_iden_1_2_false_false_double_iden_1_2_true_false_double_1_double_double_tb_128_128_8_simt_sm50_256)

9.70% 13.5765s 262876 51.646us 15.360us 197.02us cutensor_internal_namespace::contraction_kernel(cutensor_internal_namespace::KernelParam_double_iden_1_2_true_false_double_iden_1_2_true_false_double_1_double_double_tb_128_128_8_simt_sm50_256)

8.90% 12.4562s 114666 108.63us 15.648us 4.7480ms cutensor_internal_namespace::contraction_kernel(cutensor_internal_namespace::KernelParam_double_iden_1_2_true_false_double_iden_1_2_false_false_double_1_double_double_tb_128_128_8_simt_sm50_256)

7.96% 11.1327s 305932 36.389us 22.559us 76.831us void gesvdbj_batch_32x16<double, double>(int, int const *, int const *, int const *, int, double const *, int, double, double*, double*, int*, double, int, double)

5.15% 7.21024s 2439080 2.9560us 2.0480us 6.8470us void ormtr_gerc<double, int=5, int=3, int=1>(int, double const *, int, int, double*, unsigned long, double const *, int, double const *)

3.62% 5.06010s 1663200 3.0420us 1.6630us 5.8240us void sytd2_symv_upper<double, int=4>(int, double const *, double const *, unsigned long, double const *, double*)

3.43% 4.80411s 2439080 1.9690us 1.5680us 5.4390us void ormtr_gemv_c<double, int=4>(int, int, double const *, unsigned long, double const *, int, double*)

2.84% 3.97216s 1636800 2.4260us 2.1120us 5.6000us void larfg_kernel_fast<double, double, int=6>(int, double*, double*, int, double*)

2.57% 3.59984s 2123225 1.6950us 864ns 90.111us [CUDA memcpy DtoD]

2.37% 3.31885s 1663200 1.9950us 1.1520us 4.5760us void sytd2_her2k_kernel<double, int=8, int=4>(int, double*, unsigned long, double const *, int, double const *)

2.25% 3.14692s 611864 5.1430us 4.6390us 12.704us void svd_column_rotate_batch_32x16<double, int=5, int=3>(int, int const *, int const *, int, double*, int, double*, int, double const *, int*)

2.17% 3.03782s 54611 55.626us 3.1990us 315.74us void cutensor_internal_namespace::reduction_kernel<bool=1, int=2, int=6, int=256, int=1, int=256, bool=1, cutensorOperator_t=1, cutensorOperator_t, cutensorOperator_t, cutensorOperator_t, cutensorOperator_t, double, double, double, double, double>(double, double const *, double const *, cutensor_internal_namespace::reduction_kernel<bool=1, int=2, int=6, int=256, int=1, int=256, bool=1, cutensorOperator_t=1, cutensorOperator_t, cutensorOperator_t, cutensorOperator_t, cutensorOperator_t, double, double, double, double, double>, double const *, double const **, cutensorOperator_t, cutensorOperator_t, cutensorOperator_t, cutensorOperator_t, cutensorOperator_t, cutensor_internal_namespace::reduction_params_t)

2.11% 2.95838s 29720 99.541us 30.367us 1.3328ms cutensor_internal_namespace::contraction_kernel(cutensor_internal_namespace::KernelParam_double_iden_1_2_true_false_double_iden_1_2_false_true_double_1_double_double_tb_128_128_8_simt_sm50_256)

2.08% 2.91405s 1663200 1.7520us 1.5040us 4.5440us void sytd2_compute_w_kernel<double, int=8, int=1>(double const *, int, double const *, double const *, int, double*)

1.83% 2.56571s 1384952 1.8520us 992ns 6.0160us [CUDA memcpy DtoH]

1.28% 1.79144s 305932 5.8550us 5.4070us 8.4800us void svd_row_rotate_batch_32x16<double>(int, int const *, int const *, int, double*, int, double const *, int*)

1.05% 1.47607s 1157165 1.2750us 831ns 8.8960us ptxcall_anonymous21_4

1.03% 1.44738s 62378 23.203us 10.560us 57.983us void geqr2_smem<double, double, int=8, int=6, int=4>(int, int, double*, unsigned long, double*, int)

0.72% 1.00992s 252101 4.0060us 1.5680us 805.62us void cutensor_internal_namespace::tensor_elementwise_kernel<cutensor_internal_namespace::ElementwiseConfig<unsigned int=1, int=128, unsigned int=64, unsigned int=2>, cutensor_internal_namespace::ElementwiseStaticOpPack<cutensorOperator_t=1, cutensorOperator_t, cutensorOperator_t, cutensorOperator_t, cutensorOperator_t, cutensorOperator_t>, double, double, double, double>(cutensor_internal_namespace::ElementwiseParameters, int, int, cutensorOperator_t=1, unsigned int=64 const *, cutensor_internal_namespace::ElementwiseParameters, unsigned int=2 const *, cutensor_internal_namespace::ElementwiseParameters, cutensor_internal_namespace::ElementwiseConfig<unsigned int=1, int=128, unsigned int=64, unsigned int=2> const *, unsigned int=2 const **, bool, bool, bool, bool, cutensor_internal_namespace::ElementwiseOpPack)

0.71% 990.60ms 46039 21.516us 9.3440us 52.063us void geqr2_smem<double, double, int=8, int=5, int=5>(int, int, double*, unsigned long, double*, int)

0.54% 748.94ms 139738 5.3590us 895ns 11.776us void syevj_parallel_order_set_kernel<int=512>(int, int*)

0.51% 707.93ms 35644 19.861us 12.192us 34.368us void geqr2_smem<double, double, int=8, int=7, int=3>(int, int, double*, unsigned long, double*, int)

0.49% 684.11ms 542074 1.2620us 927ns 5.9200us copy_info_kernel(int, int*)

0.48% 669.92ms 298670 2.2420us 1.2470us 10.144us [CUDA memcpy HtoD]

This run was allowed to go on for longer to show that now the runtime on the GPU is dominated by useful work contracting tensors or computing factorizations.

Head to head performance fight

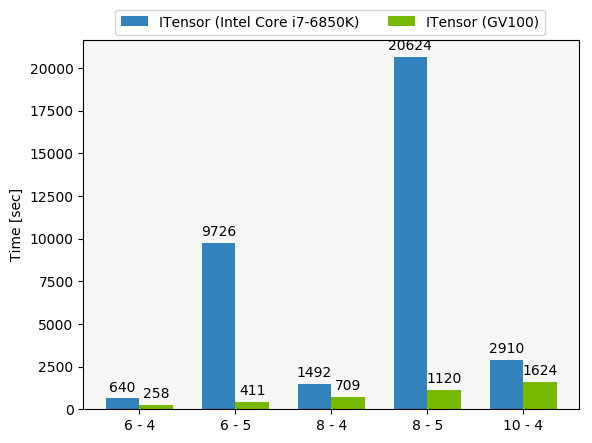

With a real physics use case to test, the nice folks over at NVIDIA ran a performance comparison for us. These are some representative (actually, rather small) simulations using our code, and you can see that the GPU acceleration is helping a lot.

The x-axis in this figure is a little opaque - it refers to varying problem sizes we might want to simulate, specifically an N by N lattice with a maximum tensor interior dimension of m - thus, N - m in the labels.

And now I'm able to run simulations that used to take a week in an hour thanks to the GPU acceleration, with no loss of accuracy so far. We've had a big success using the GPU, and so far haven't run up against the device memory limit. Having a Julia code makes it easier to maintain and easier to reason about new code as it's written. We're looking forward to using this backend to accelerate other tensor network algorithms and make it quicker to test out new ideas.

Some Takeaways

- The

CuArrays.jlpackage makes it pretty easy and pleasant to integrate the GPU into your codebase. However, there are still some pain points (in the sparse linear algebra code especially) if someone is looking for a project to contribute to. - It's important to pick a problem like this that is about 95% of the way to the perfect problem for the GPU if you want to brag without having to do much work.

- You should actually check to make sure that you aren't copying memory back and forth when you don't need to. If you are copying more than you think you should, you can try to figure out where it's coming from by inserting a

stacktracecall into thecudaMemcpycalls at theCUDAdrv.jlpackage. That should tell you the location up the call stack in your code where the copy to/from the device is triggered.

There were several things that made this transition successful:

- The simplicity of writing Julia wrappers for C code (this let us quickly interface with

CUTENSOR) - The existing ease of use of

CuArrays.jl- now it's easy to extend this to a new library, and it made writing the constructors for our own types quite straightforward - The fact that our problem was well-suited for the GPU

It's certainly true that we could have achieved the same, or possibly better, had we modified the C++ ITensor code to use the GPU. But I think it's fair to say it would have taken much more time, and would have been less accessible to other people in condensed matter physics. We were willing to settle for a slightly less than optimal speedup if the code to achieve it got written at all.

If you want to look at some of the unpleasant internals of this, feel free to check out ITensorsGPU.jl and try things out for yourself. If you're interested in learning more about tensor network algorithms, check out Miles’ site here.